The ‘Good’, the ‘Bad’ and the ‘Deobandi’ Taliban

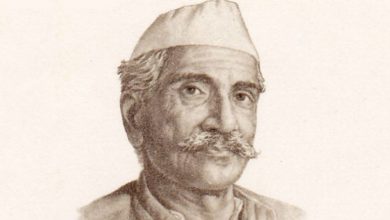

Asad Mirza

While an effort to classify the Taliban into good and bad is rather easy, the underlying reasons to classify them as Deobandi becomes a little tough and illogical.

The seizure of Afghan capital, Kabul by the Taliban and their declaration to declare Afghanistan an Islamic Emirate has again raised the spectre of The Good, The Bad and The Deobandi Taliban.

The Good and Bad Taliban

I believe the distinction between the good and the bad Taliban, was first made by Shah Mahmood Qureshi during his first tenure as the Pakistani foreign minister from 208-2011. Interpreting his statement led to the fact that Pakistan believed that the Taliban aligned to Pakistan were the good Taliban and those opposed to its policies and intervention in Afghanistan are bad Taliban.

The western media took the categorisation step forward and even American politicians like Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton used the phrase to divide the Taliban into two different categories.

While delving into the psyche of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ Taliban let’s be clear that the Taliban is not a monolithic organisation, it has various factions and tribal and clannish rivalries. In the background of the traditional Afghan society we have to understand that the smallest functioning unit is the village and the local village headman or the local Imam holds sway over the vast multitude of uneducated Afghans, thus the message which they get from the local leader is the final order for them, added to their loyalty to the local militia or the Taliban unit. In addition, the local commanders wield a lot of clout and power. Moreover, when the uneducated rural folks are handed the latest automatic weapons, they become another power unit of their own, with no link to the tag with which they were attached.

More recently, before the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the chief of the US Central Command General Kenneth F. McKenzie called the Taliban “very pragmatic and very business like”. This sounded more like ‘good’ Taliban, as they were eager to gain legitimacy before the US withdrawal and were putting out their best behaviour.

This shift is happening in the Taliban ranks too, and as per the rules set by the west and Pakistan, the factions who align with them will be the ‘good’ Taliban. And those who are still committed to the old or stubborn Taliban are termed as ‘bad’ Taliban.

The Deobandi Taliban

But perhaps the most damaging sobriquet attached to Taliban is describing them as Deobandi. It shows that the people who describe them so have no clue about the great Indian seminary of Darul Uloom, Deoband and the role, which it played in tempering the Muslims sentiments on secular lines in addition to its immense contributions to the freedom struggle of India.

Barbara Daly Metcalf, an expert on the history of South Asia, especially the colonial period and the history of the Muslim population of India and Pakistan, in her book Islamic Revival in British India, Deoband 1860-1900 (February 2002) describes Deoband at the turn of the millennium emerging into public consciousness because of the association of the leadership of the Afghan Taliban regime with the Deobandi Ulema of Pakistan.

She is of the view that many of the Taliban, whose very name described them as madrasa ‘students’, had studied in Deobandi seminaries in the Pakistan frontier provinces when, from the 1980s on, millions of Afghans had settled as refugees in that area. And based on this fact collectively calling all Taliban as Deobandi Taliban and casting aspersions on the Indian Deoband seminary is complete ignorance of Islam in the sub-continent.

The surge in the number of madrasas coincided with the influx of some three million Afghan refugees, for whose boys these madrasas provided the only available education. One school in particular, the Madrasa Haqqaniya, in Akora Khatak near Peshawar, trained many of the top Taliban leaders. These sometime students were shaped by many of the amended Deobandi reformist causes, all of which were further encouraged with Wahabi interpretation by Arab volunteers in Afghanistan.

These causes included rigorous concern with fulfilling rituals related to daily prayers and reciting the Holy Quran; opposition to custom laden ceremonies such as weddings and pilgrimage to shrines, along with practices associated with the Barelvi and Shi’a minority; and a focus on seclusion of women as a central symbol of a morally ordered society.

Theirs was, according to political analyst Ahmed Rashid, ‘an extreme form of Deobandism’, which was being preached by Pakistani Islamic parties in Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan.

None of the Deobandi movements has a theoretical stance in relation to political life. They either expediently embrace the political culture of their time and place, or withdraw from politics completely. As happened in India after independence in 1947, when the leaders of Darul Uloom withdrew from the political scene completely and confined them to Deoband.

Barbara further asserts that the Deobandi madrasas on the Pakistani frontier closed periodically to allow their students to support Taliban efforts. But the historical pattern launched by the Deobandi Ulema, had treated political life on a primarily secular basis, typically, de facto if not de jure, identifying religion with the private sphere, and in that sphere fostering Islamic teachings and interpretations that have proven widely influential.

British historian and academic specialising on the history of South Asia and Islam, Francis Robinson, in an essay on the first edition of Barbara’s book, described the Deobandi movement as ‘the most constructive and most important Islamic movement of the [nineteenth) century.’

He further says that aside from Deoband’s enduring influence, it exemplifies a patter-represented in general terms in a range of Islamic movements outside South Asia as well-of cultural renewal on the one hand and political adaptability on the other.

We also need to be aware of the fact that the Pakistani madrassas, which were described as Deobandi, essentially followed the curriculum prescribed by the Indian Darul Uloom. Further some of the founders of these madrassas might have studied at the Darul Uloom, but they had no umbilical link with their alma mater, and just based on the fact that they followed a particular syllabus they were described as Deobandi, though in fact the psyche and practice of their leaders were completely different from the teachings of the Deobandi. Thus, it would be a misnomer to call the Taliban as ‘Deobandi’ Taliban.

—–Ends

Asad Mirza is a political commentator based in New Delhi. He was also associated with BBC Urdu Service and Khaleej Times of Dubai. He writes on Muslims, educational, international affairs, interfaith and current affairs.

@AsadMirzaND