Mark Tully: A Foreign Correspondent Who Became India’s Own

Andrew Whitehead on journalism, trust, and a disappearing era

By Ram Dutt Tripathi

Mark Tully was British by nationality, but Indian by instinct, habit, and journalistic conscience. To describe him merely as a “foreign correspondent” is to miss what made him exceptional — and why his journalism still matters.

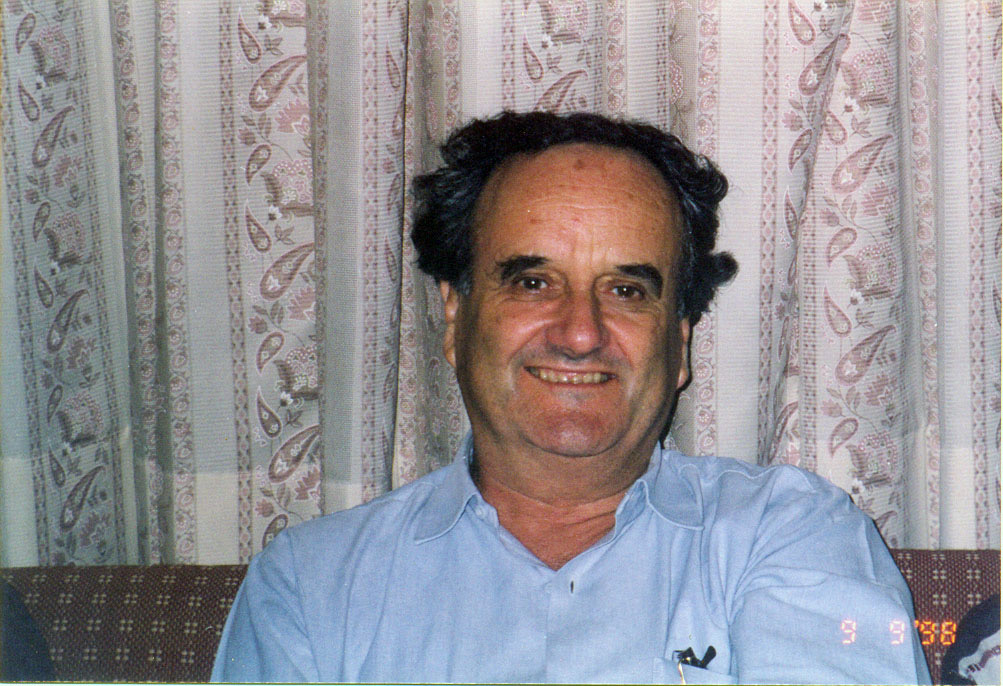

Andrew Whitehead, who worked with Tully in the BBC’s Delhi bureau in the 1990s and later headed BBC World Service News in London, remembers him as a journalist of rare humility and warmth.

“He had charisma,” Whitehead says, “but never arrogance.”

That combination shaped both Tully’s authority and the trust he commanded across India.

Not an Expat, but at Home

Tully spent nearly three-quarters of his life in India. Born here, professionally shaped here, and eventually dying here, India was not a posting for him — it was home.

Though always clear about being British, he rejected the insulated life of expatriate journalism. He travelled extensively, often by train, spoke fluent Hindi, and spoke as easily to villagers and taxi drivers as he did to ministers and officials.

This gave him something increasingly rare in modern journalism: a grounded understanding of how ordinary Indians viewed power, politics, and society.

That understanding came through not only in his reporting, but in his voice — calm, patient, and attentive.

Journalism from the Ground Up

Mark Tully was never an armchair journalist. Long before digital reporting became dominant, he insisted on being physically present at the scene of events.

He had a keen sense of news and an eye for small human details — the kind that animate stories and give them credibility.

Journalism was not his original calling. He studied theology and briefly considered the clergy before joining the BBC as an administrator. But once he entered journalism, storytelling became his natural language.

Whether in conversation or on air, he narrated events with clarity and empathy, often “painting pictures with words.”

A Voice Made for Radio

Although Tully worked in television, radio was his true medium. Television made him slightly uneasy; radio allowed his strengths to flourish.

In an era when radio had far greater reach than television in India, BBC Radio in English and Hindi enjoyed unmatched credibility. There was a widely shared belief that a story was “confirmed” only once the BBC reported it.

A defining image of that trust remains: Rajiv Gandhi at the airport, listening to the BBC on shortwave radio to confirm the news of his mother Indira Gandhi’s death.

Reporting Without Technology, But With Trust

The limitations of that era now seem almost unreal. There was no internet, no mobile phones, and only rudimentary computers. Reporters relied on cassette-based recorders and, earlier, heavy reel-to-reel machines.

News dispatches were often filed from the Central Telegraph Office. During the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992, BBC journalists worked from there.

Yet despite these constraints, the BBC consistently stayed ahead.

The reason was trust. Sources shared information with the BBC because they believed it would be used responsibly and quickly.

State-run Indian broadcasters, despite their massive reach, operated under political caution. The BBC did not.

Emergency and the Price of Truth

Tully’s reporting during the Emergency came at a personal cost. He was ordered to leave India within 24 hours — expelled from the country of his birth for telling an inconvenient truth.

The shock was immense. But, as Whitehead notes, the expulsion also proved the impact of his journalism. He would not have been targeted had his reporting been inconsequential.

After eighteen months in London, Tully returned and rebuilt the BBC’s presence in India. From 1977 onward, India remained his permanent home.

A More Open Media Environment

Whitehead contrasts that period sharply with today. In the 1990s, journalists could walk into North or South Block with a camera crew and seek interviews without elaborate permissions.

Tully interviewed leaders across the political spectrum — including Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani — in ways that are now almost unimaginable.

Even in sensitive regions like Kashmir, journalists were broadly allowed to seek multiple viewpoints. There was discomfort, but also space to report.

A strong network of BBC correspondents across Indian state capitals further strengthened Tully’s reporting, a fact he always acknowledged generously.

Leaving the BBC

In the mid-1990s, changes in BBC leadership altered the institution’s character. Under Director-General John Birt, managerial control replaced editorial autonomy.

Tully was removed as Delhi Bureau Chief and redesignated South Asia Correspondent. Disillusioned, he publicly criticised the new leadership, accusing it of running the BBC through fear.

The criticism made headlines. Pressure followed. Tully resigned — he was not dismissed.

At 59, he continued broadcasting as a freelance, hosted programmes on BBC Radio 4, and made documentaries. But he never left Delhi.

Lessons for Today

For young journalists, Whitehead identifies three enduring lessons from Tully’s life:

- Humility — journalism is about people, not the journalist

- Proximity — reporting improves when one goes closer to the story

- Kindness — warmth and empathy build credibility

Mark Tully was not a textbook journalist. But his integrity, humanity, and storytelling authority made him incomparable.

Conclusion

Mark Tully represented a form of journalism rooted in trust, access, and moral courage.

At a time when journalism is increasingly shaped by speed, spectacle, and pressure, his life reminds us that the deepest strength of reporting lies not in technology, but in integrity — and in caring deeply about the society one reports on.

Editor’s Note:

This article is based on an extended conversation with Andrew Whitehead, who worked closely with Mark Tully in the BBC’s Delhi bureau and later led BBC World Service News in London. The piece reflects on a period of Indian journalism marked by institutional credibility, editorial courage, and close engagement with society — qualities increasingly under strain today.