“Let Gandhi the Lawyer Be Remembered”: Justice Muralidhar’s Insightful Address on Mahatma

Dr Sanjoy Singha

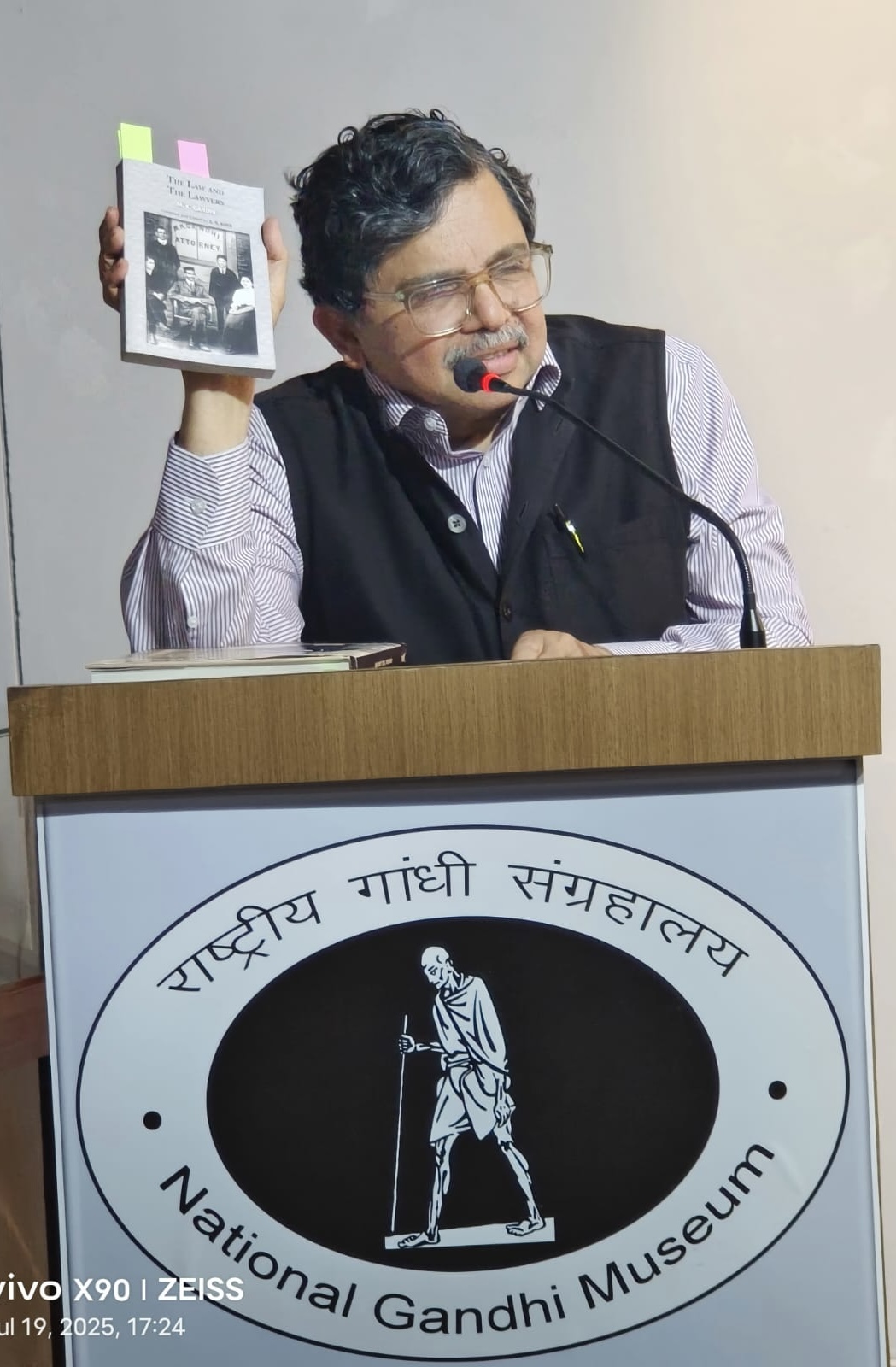

New Delhi, July 19 – In a deeply reflective and thought-provoking lecture delivered at the National Gandhi Museum, Hon’ble Dr. Justice S. Muralidhar (Retd. Chief Justice, Odisha High Court) illuminated a lesser-explored dimension of the Mahatma Gandhi —as a lawyer committed to truth, ethics, and justice.

The event was part of the monthly Gandhi Lecture Series, attended by legal luminaries, researchers, students, and Gandhian scholars from across the country.

The meeting was presided by the Shri Rajiv Shakdher, former chief justice, High court of Himachal Pradesh.

Speaking on the theme “Gandhi as a Lawyer”, Justice Muralidhar traced the trajectory of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s legal journey from his early days in London and Bombay to his transformative work in South Africa.

What emerged was a portrait of Gandhi not merely as a nationalist or a saint, but as a lawyer of profound conscience—a figure whose legal practice sowed the seeds of his later leadership in India’s freedom struggle.

The Law as a Moral Calling

Justice Muralidhar began by challenging the conventional view of Gandhi as someone who abandoned law for politics. “On the contrary,” he asserted, “law was Gandhi’s first training ground in service, truth, and resistance.”

Gandhi’s training at Inner Temple in London and his short stint in Bombay’s legal circuit revealed to him the limitations of a colonial legal system that often prized form over fairness.

It was in South Africa, however, that Gandhi truly came into his own as a legal practitioner.

Facing institutionalized racism and widespread injustice against the Indian diaspora, Gandhi developed what Justice Muralidhar termed a “conscience-driven practice of law”

—An early form of what we now recognize as public interest lawyering.

Champion of the Oppressed

In South Africa, Gandhi represented indentured Indian laborers and small merchants who had virtually no voice in a racially biased legal system. He offered low-cost or free legal services, preferring settlement and dialogue over litigation.

“Gandhi discouraged unnecessary lawsuits. For him, the lawyer’s duty was not just to win cases, but to resolve conflicts with honesty and justice,” Justice Muralidhar explained.

He recounted an incident where Gandhi, upon discovering his client was dishonest, refused to continue defending the case, thereby sacrificing a sure victory. “How many lawyers today would walk away from a dishonest client? That’s the ethical bar Gandhi set,” Muralidhar added.

A Blueprint for Public Interest Law

Justice Muralidhar described Gandhi’s legal strategy as a precursor to public interest litigation (PIL).

By mobilizing collective legal action, filing petitions on behalf of vulnerablegroups, and framing legal issues in moral terms, Gandhi laid the groundwork for law as a tool for social change.

“Gandhi may not have used the phrase ‘constitutional morality’—but he practiced it before it became fashionable,” said Muralidhar, evoking strong appreciation from the legal scholars in attendance.

Law as a Weapon of Truth

Drawing extensively from Gandhi’s autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with truth, Justice Muralidhar highlighted how truth (satya) and nonviolence (ahimsa) were not merely political ideas but central to Gandhi’s legal worldview.

Gandhi believed that a lawyer must first and foremost be truthful, even at the cost of losing a case. “Legal ethics for Gandhi was not just a professional requirement, but a spiritual discipline,” Justice Muralidhar observed. “His respect for the court, punctuality, fair drafting, and truth-based argumentation were foundational to his legal method.”

From Barrister to Bapu

The lecture also explored how Gandhi’s legal career informed his transformation into a mass leader. “His legal mind helped him navigate colonial bureaucracy, draft charters, negotiate with Viceroys, and structure mass movements like a courtroom debate,” Justice Muralidhar pointed out.

Gandhi’s skills as a lawyer—listening, reasoning, negotiating—translated seamlessly into his work as a civil rights leader, shaping tools like satyagraha, hartal, and constructive dialogue with the British Empire.

Relevance for Today’s Legal System

In a powerful closing appeal, Justice Muralidhar urged lawyers, judges, and students to revisit Gandhi’s legal legacy—not merely as history, but as a living philosophy.

“Today, when the law is sometimes used to suppress rather than liberate, we must remember Gandhi the lawyer, who saw law as a moral instrument, not a weapon of power.”

The audience, comprising students, senior advocates, and social workers, responded with resounding applause.

Questions ranged from the erosion of ethical standards in modern litigation to the role of law schools in nurturing value-based legal education.The event was hosted by the National Gandhi Museum, which has been organizing the

Gandhi Lecture Series to foster critical dialogue on Gandhian principles in contemporary India.

The lecture was live streamed and is available online on YouTube. A booklet compiling key lectures, including this one, is under preparation, according to museum officials.

Justice Muralidhar’s lecture was not just a tribute to Gandhi, the lawyer—it was a clarion call to restore ethics, compassion, and truthfulness to legal practice.

At a time when the judiciary faces questions about its independence and lawyers are often seen as adversarial warriors, Gandhi’s example reminds us that the law can also be a path to peace and dignity.