Power Consolidation in China’s Communist Party

The 20th Congress of the China’s Communist Party will begin on 16 October

Asad Mirza

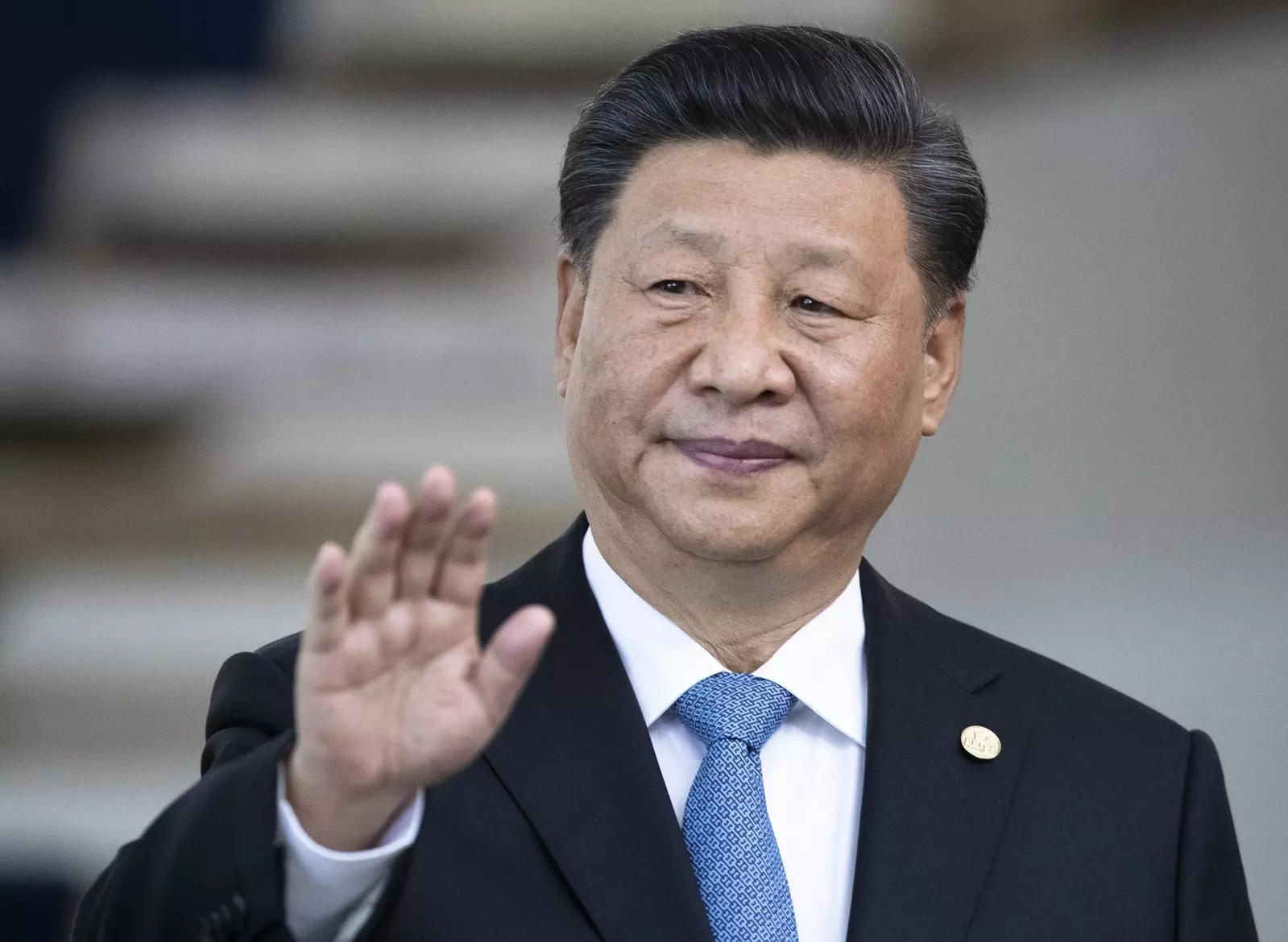

The 20th Congress of the China’s Communist Party will begin on 16 October, a five yearly exercise. This time it is expected to approve Xi Jinping as country’s paramount leader for the third unprecedented time.

Recent rumours of a military or a political coup in China seem to be largely unsubstantiated and unreliable. They can be dismissed as based on the fact that the current leadership has in the past week acted harshly against what it called a “political clique” against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and this is not a new phenomenon and more or less, happens before every major party conference.

Last week, China’s former Deputy Public Security Minister Sun Lijun, former Justice Minister Fu Zhenghua and three former police chiefs of Shanghai, Chongqing and Shanxi provinces were jailed for life, after being denounced for “seriously damaging the unity of the party”. This was also intentioned as a message to anti-Xi forces to fall in line and support the current leader.

Though there is little doubt that Xi is poised to win five more years as China’s paramount leader, extending a tenure that began in late 2012, there is still uncertainty about how much influence he will wield over the formation of a new power structure. But the Congress will also end speculations about China’s rising stars on the horizon.

20th CCP Congress

Xi, 69, is widely expected to be exempt from the party’s informal “seven up, eight down” rule that ordinarily requires senior officials who are 68 or older to step down.

The rule will also not be applicable to everyone in the party’s inner circles, meaning at least two of the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee and half of the 25-strong Politburo will probably retire.

But the new structure could be even more innovative, as there have been suggestions that Xi may shrink the CCP standing committee to five members, giving him more freedom, and replace some of those members who have yet to reach 68 by having them retire to make way for his supporters.

CCP over the years

Mao Zedong overshadowed the Chinese political system for first 27 years of the CCP rule. Until his death in 1976 Mao had the final word on every state and party matter including deciding the leadership’s formation, enlarging or shrinking the size of the Politburo and the standing committee at will.

In 1978, Deng Xiaoping became paramount leader. Though considered very powerful, yet he also had to consult with seven other senior party members, a group known collectively as the “Eight Elders” or the “Eight Immortals”.

By 1989 with Jiang Zemin’s rise to power and after Deng Xiaoping’s death in 1997, consensus politics had started to take hold in the CCP. The top party leadership introduced channels to balance and institutionalise power, and to improve accountability and governance.

Jiang, for instance, introduced the “seven up, eight down” practice. Jiang’s successor Hu Jintao, from 2002 to 2012 further institutionalised Consensus rule, through intra-party democracy, through straw polls and competitive elections for the members of the party’s Central Committee.

Xi’s tenure

This led to June 2007, about four months before the party’s 17th Congress at which Xi was inducted into the Politburo Standing Committee, when a straw poll was held for the first time among all Central Committee members and other leading officials to recommend provisional candidates for the new 25-member Politburo.

Five years later in May 2012, the party’s elite officials again met in Beijing to make recommendations on candidates not only for the 25-member Politburo, but more importantly the Standing Committee, also. This poll was then used as a benchmark to shape the new leadership line-up for the 18th Congress, at which Xi emerged as party supremo.

However, Jinping did not like the previous electoral methods. Before the party’s 19th Congress in October 2017, from which Xi emerged as a stronger leader having secured a second term, the party leadership found serious faults with the straw poll method. Ahead of the 19th Congress, Xi opted instead for face-to-face meetings to select the new leadership.

The most obvious prerequisite for being elected to the new party structure is to be seen as being loyal to the current leader and party leadership besides possessing experience in key areas like ability to handle crises, a proven track record of competency, the ability to earn Xi’s trust, a highly educated background and strong regional leadership experience.

In the forthcoming Congress, many contenders for top posts also share close connections to Xi and his trusted aides and have professional expertise in areas such as technology and business.

Several of Xi’s former associates in Zhejiang and Fujian provinces are expected to be promoted to even higher positions. One such high-flyer is Shanghai party chief Li Qiang, and the other one is He Lifeng, who is in charge of the National Development and Reform Commission.

Some other regional chiefs are also seen as strong candidates for advancement, even though they have not been associated directly with Xi before he became president. This includes Guangdong party boss Li Xi; Fujian party secretary Yin Li and Shanghai mayor Gong Zheng; Liu Haixing, a seasoned diplomat; Liu Jieyi, currently Head of the State Council’s Taiwan Affairs Office, and might be the next Chinese foreign minister; Liu Zhenli, commander of the PLA’s ground forces and Shen Yiqin, one of the few women in a provincial party leadership role or on the Central Committee, Shen is a front runner to succeed Sun Chunlan as a Politburo member when she retires. Vice-Premier Sun is currently the only woman in the Politburo.

A confident Xi looking set to secure his third term as the party chief at the Congress, has plans to achieve the target of creating a more modern socialist China by 2049 – the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and to accomplish this dream he needs a new leadership line-up which will help him take forward and deliver that promise or a legacy which we would want to leave behind.

—–Ends

Asad Mirza is a political commentator based in New Delhi. He was also associated with BBC Urdu Service and Khaleej Times of Dubai. He writes on Indian Muslims, educational, international affairs, interfaith and current affairs.

@AsadMirzaND