Bapu Kuti at Sevagram: Gandhi’s Sustainable Architecture Revisited Through Archival Drawings

Archival Architectural Drawings Exhibition at Sevagram Ashram

By Dr. Siby K. Joseph

After resigning from the Indian National Congress in 1934, Mahatma Gandhi chose Wardha as the centre of his constructive work. He established the All-India Village Industries Association and shifted to an estate donated by Jamnalal Bajaj. The estate was renamed Maganwadi in memory of Maganlal Gandhi.

Gandhi’s Move from Politics to Village Life

Yet Gandhi was searching for something deeper than an institutional base — he wanted to live in a typical Indian village.His British disciple Mirabehn identified a remote village called Segaon, about four miles east of Wardha. Situated roughly 75 km from Nagpur in central India, Segaon embodied the rural simplicity Gandhi sought.

In a letter dated March 19, 1936, Gandhi wrote to Jamnalal Bajaj:

“As little expense as possible should be incurred in building the hut, and in no case should it exceed Rs. 100.”

This was not merely frugality — it was philosophy in action.

Settling in Segaon: Service Before Comfort

After visiting Segaon in April 1936, Gandhi declared his intention to live among the villagers:

“I shall try to serve you by cleaning your roads and surroundings… If you will cooperate with me I shall be happy; if you will not, I shall be content to be absorbed among you.”

On April 30, 1936, Gandhi and his colleagues walked from Maganwadi to Segaon. Initially, he stayed in a temporary bamboo-mat shelter under a guava tree.

Construction of his hut proceeded under the supervision of Mirabehn. Built entirely with local materials, the structure reflected simplicity, functionality and ecological wisdom.

Gandhi described it in a letter:

“My hut has thick mud walls… I think you will fall in love with the hut and the surroundings.”

The structure measured 29 x 14 feet, with a 7-foot verandah running around it. Mud walls, local materials, minimal cost — the hut embodied self-reliance.

From Segaon to Sevagram

The first residence later became known as Adi Niwas. Additional huts were built:

- Ba Kuti for Kasturba Gandhi

- Mirabehn’s hut, later known as Bapu Kuti

By 1940, Segaon was renamed Sevagram (“village of service”). In 1941, due to overcrowding, Gandhi shifted into Mirabehn’s hut — the now iconic Bapu Kuti.

This modest cottage became the nerve centre of the freedom movement. National and international visitors met Gandhi here. The hut remains preserved in its original condition.

Architecture as Philosophy

Gandhi’s residences — Adi Niwas, Ba Kuti and Bapu Kuti — were built entirely from materials sourced within a 75-kilometre radius.

The primary construction material was Garhi Mitti, a composite of mud, cow dung and wheat husk layered over a bamboo grid. The bamboo framework functioned like “green steel,” providing tensile strength and flexibility.

Though visually modest, the engineering was sophisticated:

- Flexible bamboo grid for seismic resistance

- Thick mud walls for thermal regulation

- Clay floors for cooling

- Red clay tile roofing

This was sustainable architecture decades before the term became fashionable.

The huts were not symbolic poverty — they were conscious design choices rooted in ecological ethics and decentralised economics.

Ivan Illich on the Spiritual Geometry of the Hut

In 1978, philosopher Ivan Illich reflected on Bapu Kuti:

“The hut proclaims the principle of love and equality for everyone.”

He described its spatial flow — an entrance space for preparation, a central gathering room, Gandhi’s work corner, a guest space, a sick room, verandah, and bathroom — all organically connected.

The hut was architecture as moral geometry.

Gandhi’s Places: Architectural Documentation

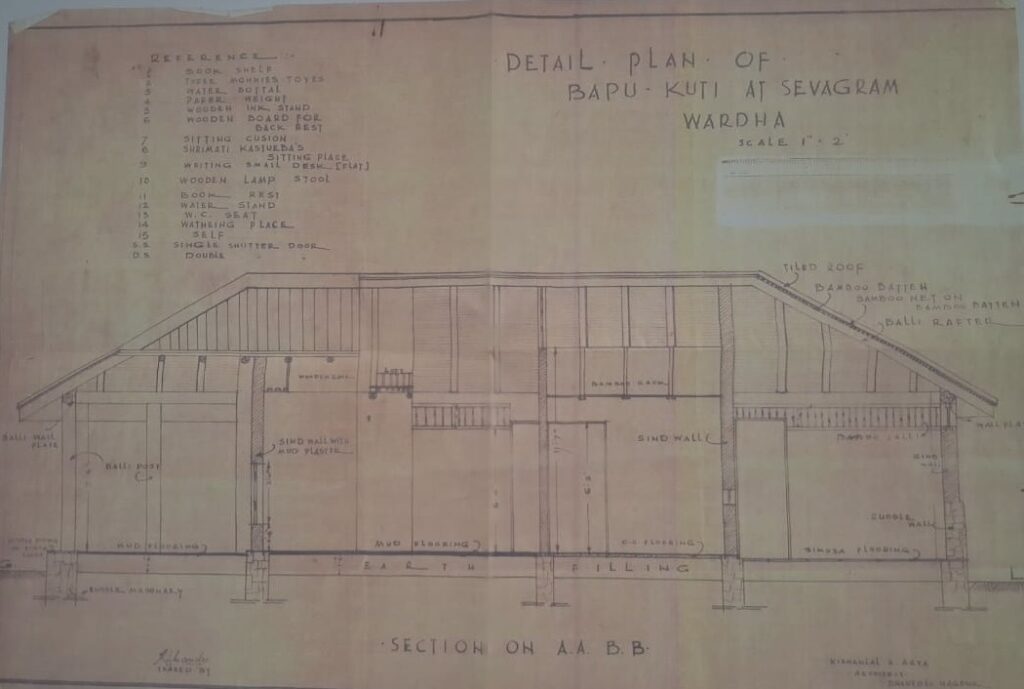

In 2004, the Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust published Gandhi’s Places: An Architectural Documentation. Edited by architects Neelkanth Chhaya and Riyaz Tayyibji, along with Gandhian scholar Tridip Suhrud, the volume includes 131 architectural drawings of Gandhi-associated sites, including Kochrab, Sabarmati and Sevagram.

The documentation reveals how Gandhi’s built environments mirrored his ideological evolution — from community living to rural reconstruction.

2026 Exhibition: Bapu Kuti Reimagined

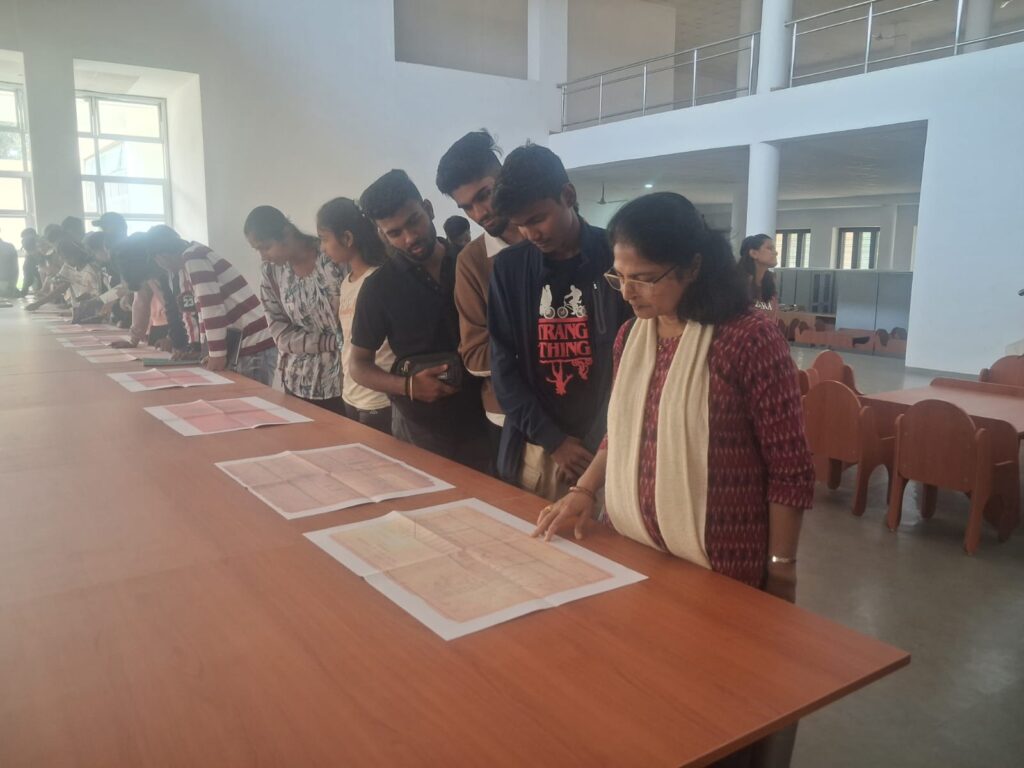

On January 12, 2026, coinciding with the visit of faculty and students from Vidya Pratishthan’s School of Architecture, Baramati, the Sri Jamnalal Bajaj Memorial Library and Research Centre for Gandhian Studies organised an exhibition titled “Architecture of Bapu Kuti.”

The exhibition featured:

- Archival drawings from the 1960s

- Technical specifications of foundation, plinth, walls and roof

- Elevation drawings (front, west and north)

- Detailed site plans

- Archival video footage

Forty-one participants, including five faculty members, attended a dedicated screening session. Dr. Siby K. Joseph addressed the gathering, and Shri Piyush Shah delivered the vote of thanks.

The exhibition demonstrated that Bapu Kuti is not merely a preserved relic — it is a living lesson in sustainable architecture.

Why Sevagram Matters Today

At a time when Indian villages are rapidly replacing mud homes with concrete structures, Sevagram stands as a reminder of:

- Low-carbon construction

- Climate-responsive design

- Community-centred spatial planning

- Minimalist living

Gandhi’s huts show that sustainability is not a technological invention — it is a civilisational memory.